Airbus and Safran Propose New Ariane 6 Design, Reorganization of Europe’s Rocket Industry

European space-hardware builders Airbus and Safran have proposed that the French and European space agencies scrap much of their previous 18 months’ work on a next-generation Ariane 6 rocket in favor of a design that includes much more liquid propulsion.

The two companies further said they will merge their rocket divisions into a single joint-venture entity that would expand to take over Ariane production and sales.

The proposal, which has the apparent backing of the French government and which one European government official said would detonate a “Big Bang” in Europe’s rocket sector, has forced its way onto the agenda of the European Space Agency, which has agreed to review it July 16, according to European government officials.

Airbus and Safran’s surprise move came June 16 during a ceremony at France’s Elysee Palace in the presence of French President Francois Hollande.

The joint venture, split 50-50 between Airbus and Safran, means Airbus would no longer be prime contractor for Europe’s Ariane rocket. The role would be assumed by the new company. Airbus and Safran together hold about 43 percent of the equity in Evry, France-based Arianespace, which currently markets and operates Ariane vehicles. The companies propose to purchase the 35 percent Arianespace share held by the French space agency, CNES.

Followed to its logical end, the proposal means Europe’s launch vehicle development would become a private-sector affair based on performance requirements given by the government and the commercial sectors. Whether CNES or ESA would need to retain a launcher division is an open question. Government agencies, too, are being asked to reduce their rocket-related expenses.

Changes are afoot for Arianespace as well. The company’s chief executive, Stephane Israel, briefing journalists July 17 here, said his company is well aware that it cannot escape a restructuring as part of the broader reorganization of the launcher sector.

ESA, CNES, Germany’s DLR space agency and others have said the design of a new Ariane 6 rocket, and approval of an upgraded Ariane 5, should be used as occasions to reorganize Europe’s rocket industry so that it can better compete by lowering costs. Implicit in this is an acknowledgement that the 12,000-odd workforce building Ariane vehicles would be cut approximately in half.

“It’s all about enhancing the competitiveness of our space launcher business going forward,” Airbus Group Chief Executive Tom Enders said in a June 16 statement. “Our agreement with Safran is the starting point of an exciting journey towards a more integrated, more efficient and hence more profitable launcher business in Europe.”

French government officials said the last time a French president held an audience with the launch vehicle sector was in the early 1970s. Following the photo session, Hollande’s office issued a statement congratulating Airbus and Safran on their joint-venture decision, but also saying the space sector counts 16,000 jobs in France alone.

The two companies are asking that ESA governments, scheduled to meet in December, confirm their commitment to finishing work on an upgraded Ariane 5 rocket to give the vehicle a restartable upper stage and more payload-carrying power. The upgrade is intended to permit Ariane 5 to better compete with Space Exploration Technologies Corp. of the United States for lighter satellites, and with Russia’s Proton rocket for heavier satellites.

The upgraded Ariane, called Ariane 5 ME, would continue the current Ariane 5 business model of launching two telecommunications satellites at a time into geostationary transfer orbit. If the remaining upgrade work is funded by ESA governments in December, at a cost of about 1.2 billion euros ($1.6 billion), Ariane 5 ME could be in service starting in 2018.

ESA governments, under heavy pressure from France, in November 2012 agreed to start early work on a next-generation Ariane 6 rocket in parallel with Ariane 5 ME, with both vehicles sharing the restartable Vinci upper stage.

As agreed to by ESA and CNES, the Ariane 6 design being studied for the past 18 months featured solid-fueled first and second stages, the Vinci liquid-fueled upper stage and two strap-on solid-rocket boosters that would be virtually identical to the first and second stages.

The economies of scale in building so many identical solid-fueled stages was key to the design-to-cost approach to create a rocket that would reach the ESA-mandated price point of 70 million euros per launch.

But that vehicle never won endorsement from Germany, whose industry had focused on liquid-fueled technology and whose government never liked the lack of modularity in the Ariane 6 vehicle.

The solid-fueled Ariane 6 drew heavily on French and Italian specialties. But with France intending to pay no more than 50 percent of the development costs, questions were raised as to Italy’s ability to fund its sizable share.

Germany was not alone in voicing concerns about the design. Commercial satellite fleet operators — whose business is indispensable to the financial viability of Arianespace — said an Ariane 6 with a maximum payload capacity of 6,500 kilograms would be unable to launch two 3,500-to-4,000-kilogram satellites at a time when such pairings were available. That would make the vehicle less competitive, these satellite operators said in a letter to ESA.

ESA had turned aside these critiques in recent months, saying all alternatives to the mainly solid-fueled design had been studied, and none met the ESA test for acceptability — 70 million euros to launch, a development cost as low as possible, and a service introduction of around 2020.

Government and industry officials said the Airbus/Safran proposal features two Ariane 6 designs. This would replace the current Ariane 5 and the Europeanized Russian Soyuz rocket that now launches more European government satellites than does the heavy-lift Ariane 5 because the satellites are better suited to a midrange rocket.

One Ariane 6 would launch payloads weighing between 3,000 and 7,000 kilograms into orbit, with the focus on the European government market. The other would have a lift capacity of up to 8,500 kilograms and would be used for commercial launches, both single- and dual-launch versions.

The announcement appeared to catch ESA off guard. The agency has been saying for months that only one Ariane 6 version was on the table. Then, in mid-May, France’s space minister, Genevieve Fioraso, told reporters in Berlin that France was willing to consider alternative designs if they met the cost and schedule requirements.

The new design makes it much more likely that Ariane 6 will receive major financial backing from Germany, even if France retains responsibility for about 50 percent of the total development package.

Johann-Dietrich Woerner, chairman of DLR’s executive board, issued a measured statement June 17, saying industry consolidation “can help to achieve our objectives.”

ESA Director-General Jean-Jacques Dordain said in a statement that he welcomed the joint-venture proposal as a first step toward industry consolidation. As to the new Ariane 6 design, Dordain said it would be evaluated alongside the original design as ESA moves toward its December ministerial conference for final decisions.

CNES President Jean-Yves Le Gall, in a June 17 interview, said he has no problems, in principle, with a new Ariane 6 design, so long as it meets the development cost, production cost, and in-service-schedule requirements set by CNES and ESA.

“When I first arrived at CNES I didn’t like the [solid-fueled] Ariane 6 design,” Le Gall said. “But it turned out to be the only one that met the criteria that had been set.”

Le Gall said the two companies’ proposal to scrap the idea of a new launch pad for Ariane 6 — estimated price: 750 million euros — is a good idea that had already been incorporated into the latest iteration of the solid-fueled Ariane 6 design.

Whether the new version proposed by the two companies can be produced and launched for 70 million euros is a big question that has not been answered, Le Gall said. Also unknown is whether its development will cost more than the estimated 3.25 billion euros for the earlier Ariane 6 design.

Other questions remain. Will the French government accept a rocket design that cuts France’s launch vehicle employment by 50 percent or more? One French industry official said all have agreed that this will happen in the decade between now and the arrival of the Ariane 6, but that no interest is served in headlining the fact.

“If you start a debate by saying there will be blood everywhere, the idea won’t go far,” this official said. “But we all know what the end result is.”

Le Gall had said Europe’s network of 20-plus Ariane integration sites needs to be cut to perhaps three — one each in France, Germany and Italy. Italy’s role in solid-rocket production with the Italian-led Vega small-satellite launcher had been one argument for the earlier Ariane 6 design. The Airbus-Safran announcement is silent on which sites would be kept, and which would be closed.

Similarly, the two companies are still not clear about whether the Ariane 5 ME will be able to survive without the annual 100 million euros in price supports that allow Arianespace to balance its books. Government officials have said previous industry commitments on this point have been riddled with conditions that make the commitment less serious.

-

Latest

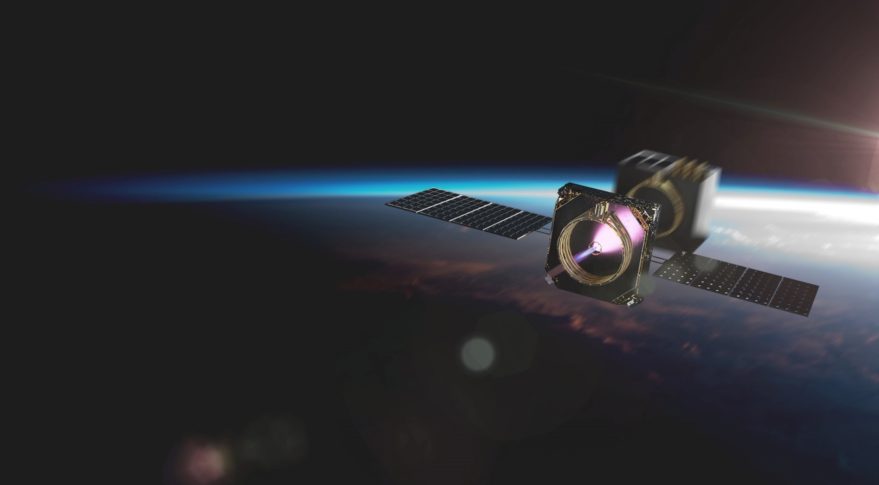

Momentus valuation slashed in revised SPAC deal

Momentus valuation slashed in revised SPAC dealWASHINGTON — A special purpose acquisition corporation (SPAC) has revised its agreement to merge with in-space transportation company Momentus, cutting the value of the deal in half.Stable Road Acquis...

-

Next

Space Development Agency celebrates launch of its first satellites

Space Development Agency celebrates launch of its first satellitesWASHINGTON — The Defense Department’s space agency on June 30 hailed the deployment of its first missions which flew to orbit on a SpaceX rideshare carrying 88 small satellites.“Today’s missions will...

Popular Articles

- Rocket Power (TV Series 1999–2004) - Rocket Power (TV Series ...

- technique - What is the definition of 'playing in the pocket ...

- "Pocket rockets," in poker Crossword Clue Answers, Crossword ...

- 5 Sex Toys Every Man Should Own, Use & Use Again - LA Weekly

- Pocket Holsters: 11 Options For Easy Everyday Carry (2021 ...

- What is Elton John's most successful song? (Celebrity Exclusive)